State False Claims Acts

When the topic of whistleblower actions comes up, the federal False Claims Act (FCA) often dominates the conversation. The FCA was originally passed in 1863 in response to rampant fraud against the United States during the Civil War. When drafting the FCA, Congress drew on the nation’s rich history of qui tam enforcement dating back to, and through, the ratification of the federal Constitution. The qui tam provisions of the FCA permit a private citizen, called a relator, to initiate litigation on behalf of the Government in order to recoup fraudulently obtained funds from those involved in the submission of false claims for payment to the Government. Although qui tam actions are instituted by private citizens, the Government maintains an active role, and holds ultimate control, in all qui tam litigation. When a qui tam action results in a recovery for the United States, the relator is entitled to receive between fifteen and thirty percent of the proceeds of any recovery. The FCA has been immensely successful in protecting the public fisc, having resulted in over $78 billion in recoveries since 1986, with $2.9 billion recovered in 2024 alone.

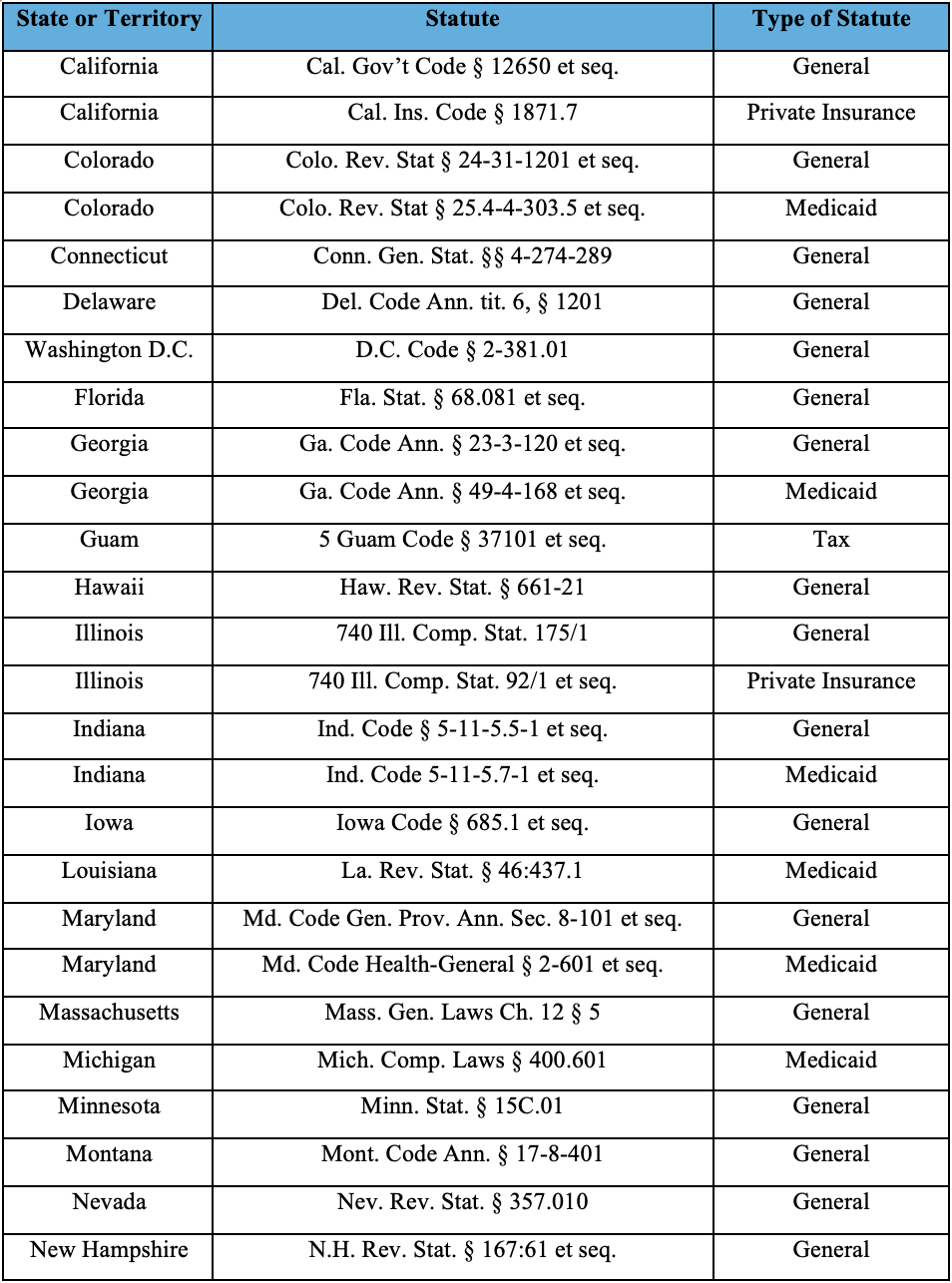

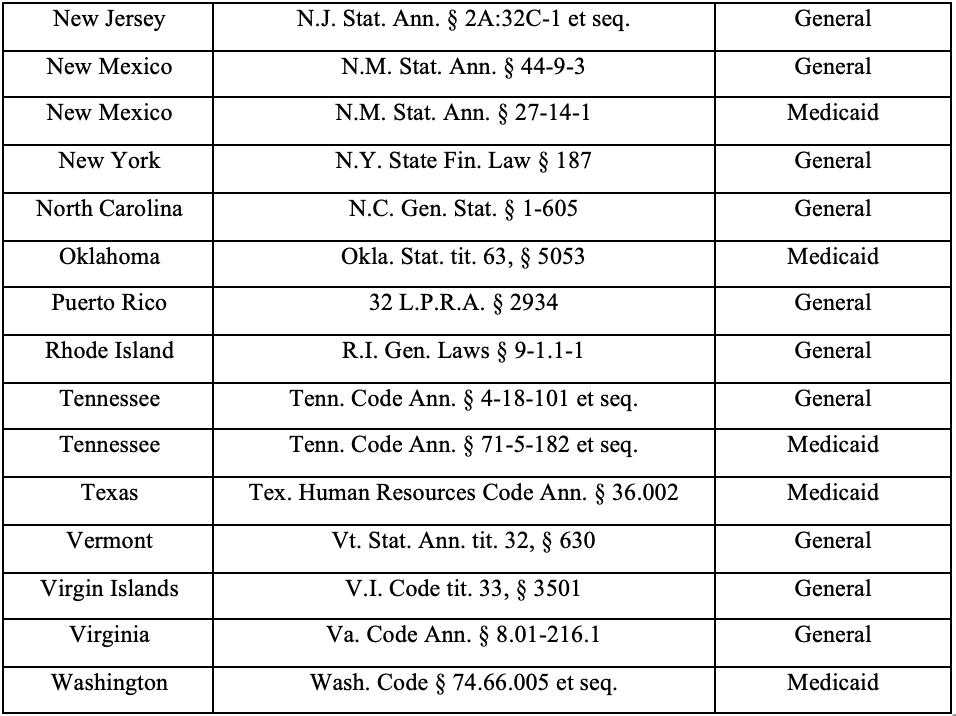

Seeing the success of the federal FCA, 33 states or territories have also passed false claims acts with qui tam provisions empowering whistleblowers to come forward with information to redress fraud committed against the state or territory. Many of these statutes mirror the federal FCA, with the exception that they seek redress of frauds committed against the specific state, rather than against the federal government. While many of the statutes follow the form and substance of the federal FCA, there can be important differences. For example, the federal FCA permits a cause of action based on any fraudulent claim to the Government. But the qui tam statutes in Texas and Oklahoma only permit private citizens to bring claims based on Medicaid fraud. Other states, such as Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Maryland, New Mexico, and Tennessee have both a “general” false claims act and a Medicaid-specific false claims act. Adding more tools to the mix, California and Illinois have private insurance fraud statutes, permitting whistleblowers to bring claims seeking to redress fraud perpetrated against private insurers. In sum, there are 41 false claims acts pertaining to specific states or territories, as listed in the chart below:

Additionally, the House of Representatives for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania approved a bill on July 9, 2025 seeking to create an FCA modeled after the federal statute. The bill is subject to vote by the Pennsylvania senate. The legislature for the State of Ohio is likewise considering a state false claims act.

Adding more intrigue to the mix are states like Arkansas, which has a whistleblower statute, but does not permit qui tam actions. The Arkansas Medicaid Fraud False Claims Act provides that “[t]he court is authorized to pay a person sums, not exceeding ten percent . . . of the aggregate penalty recovered . . . for the information the person may have provided which led to the detection and bringing to trial and punishment persons guilty of violating the Medicaid fraud laws.”

It is important to keep these statutes in mind when evaluating a potential whistleblower action. For example, when presented with a potential healthcare fraud matter, it is often the case that Medicaid funds are impacted by the fraud. While the federal FCA may reach the federal share of any fraudulently obtained Medicaid payments, naming the state as another co-plaintiff, under the state’s FCA, will allow the state share of those Medicaid payments to be reached. Likewise, states often expend significant financial resources, and are vulnerable to the same types of contracting fraud as the federal government. Forgetting to consider states’ FCAs leaves money on the table, and allows potential fraudsters to escape accountability. State offices can also enhance the pool of investigatory resources and expertise available during the investigation of your client’s allegations. States can also be important allies in the pursuit of your case. It is not unheard of for a state to elect to intervene in a qui tam action, even when the federal government declines. For example, in Vierchzhalek v. Medimmune Inc., the United States declined to intervene in 2013 but in 2015 the State of New York partially intervened. 803 F. App’x 522 (2d Cir. 2020). States can also support a public disclosure veto, when needed.[1] And, of course, the members of the state team are often the best versed in the nuances of the state programs that may be implicated by the fraud your client alleges.

From a practical standpoint, bringing a claim under a state FCA is more than simply naming the state as a co-plaintiff and adding a count at the end of a complaint. It is important to remember that the states are just as much a part of any case in which they are named as the federal government. Unless a specific state FCA indicates otherwise, it is essential to make a pre-filing disclosure to the state, serve the complaint and disclosure statement on the state, and continue to dialogue with the state just as you would with the federal government. When serving a state, it is important to note that state service requirements differ from state to state.

Because of the heavy caseload federal attorneys face, it often falls on relator’s counsel to serve as the link between the state attorneys and the federal attorneys. Remember to include the state’s attorneys on important communications, including the scheduling of a relator’s interview. Similarly, should you have a case reach settlement, it is important to keep the state apprised of those negotiations and resolutions as well, as the state may also need to consent to any dismissal and ensure it receives its share of any recovery.[2] In United States ex rel. John Doe v. Mallinckrodt ARD, LLC, No. 1:18-cv-11931-PBS, the defendants paid over $123 million to the United States and over $110 million to certain Medicaid states to settle the relator’s claims. Likewise, because the state recovery may be distinct from the federal recovery, it is important to remember your client’s interest in a potential share from funds recovered by the state.

Another consideration is that when the federal government shuts down, as it did recently, state governments continue to operate. As a result of thousands of federal government employees being furloughed since October 1, some jurisdictions had issued orders staying cases in which the United States was a party.[3] This means that these cases were essentially on pause until the federal government reopened and employees were able to begin working again. However, state agencies remained open during that time and are continued to work cases, even if the matter was otherwise on hold. And, for state-only cases, those matters remained active on the docket.

It is also important to research the statutes of any state you intend to name in a complaint. While many state FCAs are modeled after the federal FCA, there are some nuances. Service requirements may vary by state. For example, when proceeding under the Illinois Insurance Fraud Claims Prevention Act, in addition to serving the complaint and disclosure statement on the Illinois Attorney General, you must also serve the State’s Attorney for the counties in which the conduct is alleged to have occurred. State seal periods may also differ. For example, in North Carolina, the initial seal period for the state action is 120 days, while in Texas it is 180. Some states require a separate motion to seal the matter,[4] while others do not.[5] Additionally, while the federal FCA does not generally reach tax fraud, some state FCAs do. For example, the New York and Washington D.C. FCAs allow actions for income tax fraud against taxpayers with income over $1 million. The Illinois statute allows claims for certain tax violations, but not income tax violations. Tax-based FCA claims are also not barred in Rhode Island, Indiana, Delaware, Hawaii, Nevada, or New Hampshire. When proceeding under a state FCA alone, it is important to be aware of these potential distinctions. When proceeding under both the federal FCA and a state’s FCA, it is important to understand the interplay of any distinctions between the two statutes. Matters become even more nuanced when proceeding under multiple state FCAs.

In sum, state FCAs are critical tools in ensuring that all fraud targeting public funds is redressed. State offices are often eager to partner with relator’s counsel, and add a wealth of resources, knowledge, and experience to the pursuit of qui tam actions. Building relationships with state offices can pay dividends and ensures that key stakeholders in the pursuit of whistleblower actions are included at the table.

[1] See e.g., Cal. Gov’t Code § 12652; Mont. Code Ann. § 17-8-403(6)(a); N.Y. State Fin. Law § 190(9)(b).

[2] See e.g., Cal. Gov’t Code § 12652(c); Del. Code Ann. tit. 6, § 1203; Va. Code Ann. § 8.01-216.5.

[3] See e.g., GO-2025-20 In Re Holding in Abeyance Civil Matters Involving the United States as a Party During Government Shutdown.pdf (last accessed October 27, 2025).

[4] See e.g., R.I. Gen. Laws § 9-1.1-4.

[5] See e.g., Cal. Rules of Court 2.571.