How Much Does a Pharmaceutical Product Cost the Government? It Depends…

Public pharmaceutical companies in the US regularly report out-sized revenues, but they face growing criticism for the very unpublic way they arrive at their drug prices. According to a survey of 1,000 American consumers, “77% believe that the consumer prices of drugs are unreasonably high,” and nearly the same number – 73% – said their opinion of pharma companies “would improve if companies were more transparent about what goes into the cost of medication.” Nowhere is that lack of transparency more evident than the prices state and federal governments pay for drugs and biologics.

In 2018, federal government spending accounted for more than 40 percent of expenditures on outpatient prescription drugs in America. The actual dollars behind those percents are staggering. In FY 2022, drugs and biologics topped the list of products purchased by the federal government through procurement contracts with $44.5 billion in obligations. And those procurement obligations do not account for the billions spent through other programs, including Medicaid or Medicare.

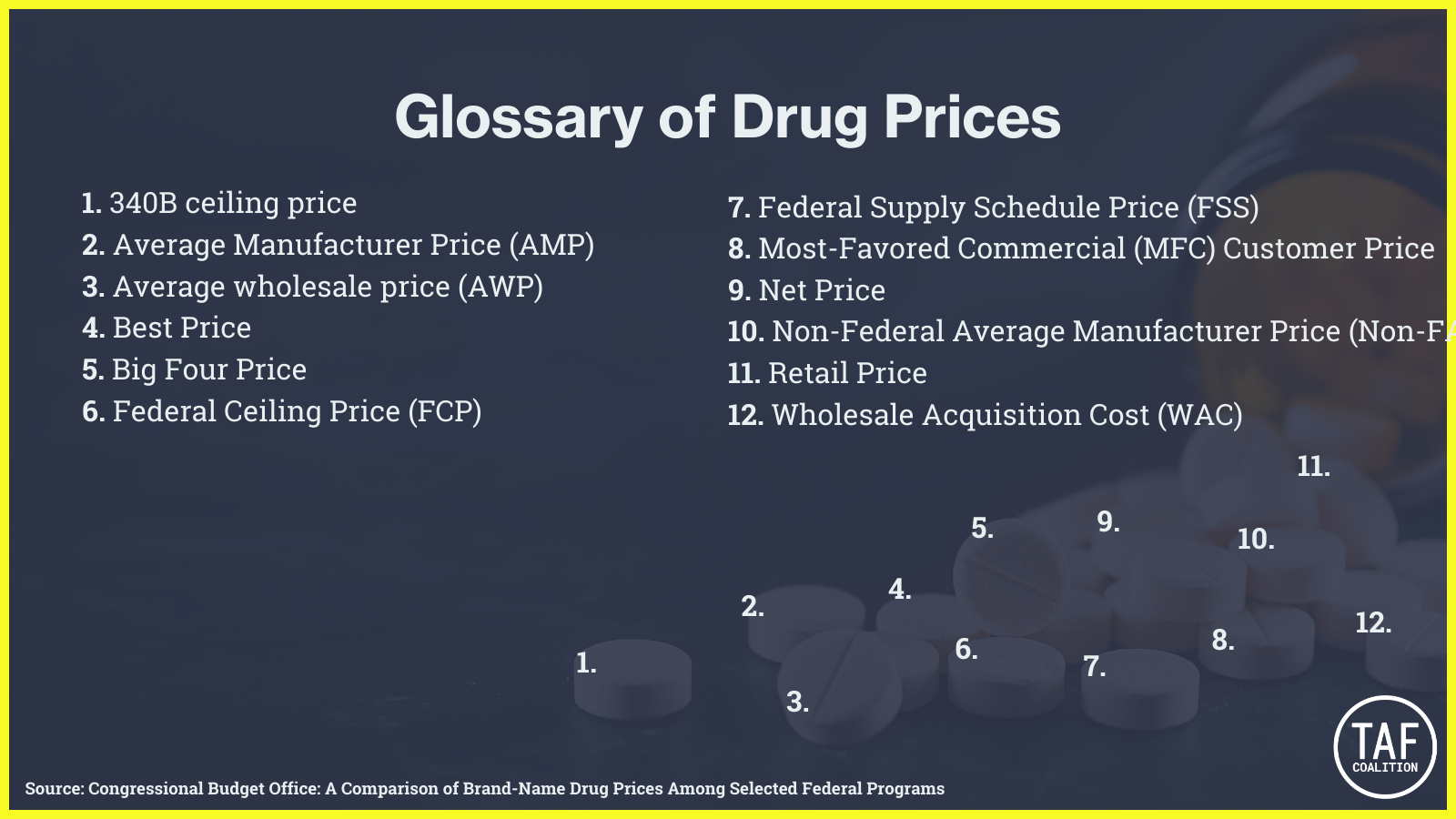

But not all government purchases are created equally. According to a Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis in 2005, “drug prices can differ considerably across government programs” and not all the pricing data is publicly available. In its updated 2021 analysis of drug pricing under selected federal programs CBO added a Glossary with more than a dozen different “prices,” including:

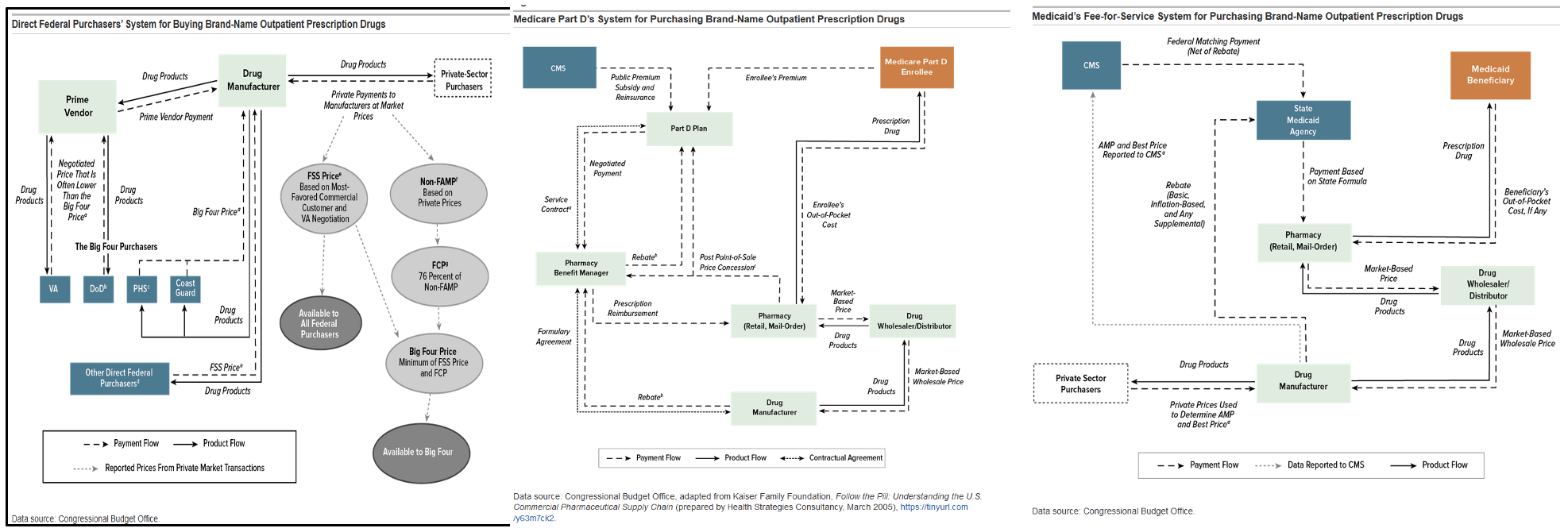

The CBO’s complex flow charts, which are supposed to clarify how pricing is determined, are virtually indecipherable to the average consumer. For example, here is the CBO’s 2021 flowchart for Direct Federal Purchasers buying Brand-Name Outpatient Prescription Drugs (like those accounted for in the procurement numbers cited above), compared to the same chart for the Medicare Part D system and Medicaid:

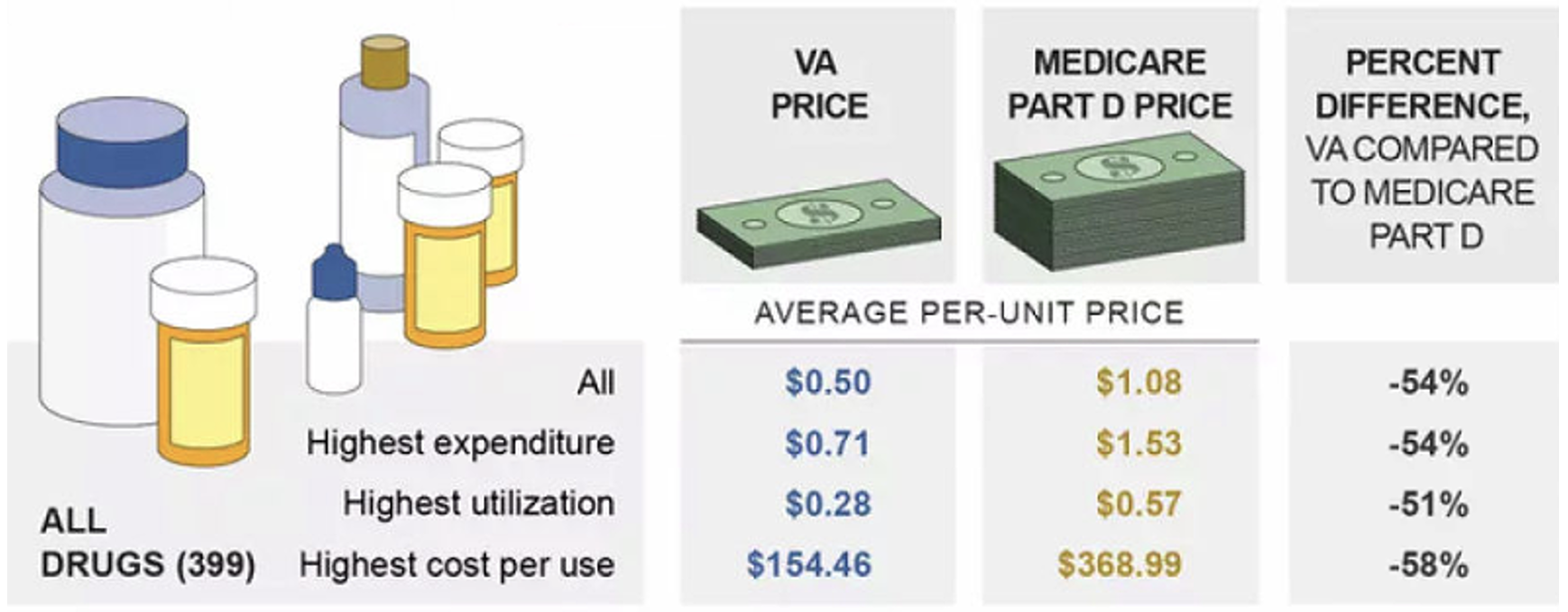

Whether the CBO’s charts provide any transparency to the process, the American taxpayer is paying wildly different prices for the same drugs depending on which government program is the purchaser. For example, in 2017, the VA (a direct purchaser) paid an average of 54% less per unit of almost 400 brand-name and generic drugs than the Medicare Part D program.

In 2022, Congress authorized a new (!) pricing program to reduce spending in the government’s largest pharmaceutical line item: Medicare Part D. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) includes provisions authorizing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to negotiate the maximum fair price (MFP) of drugs in the Medicare Part D program with drug manufacturers. If the IRA survives manufacturers’ challenges to the law itself, we will be watching to see if the U.S. government can actually reduce the costs of pharmaceuticals it is buying through the Part D program and introduce a measure of transparency to drug costs more generally.

For all the U.S. drug pricing programs introduced to date, whistleblowers have played critical roles in exposing the manufacturers, distributors, pharmacies, and providers defrauding the government through pricing fraud. From AWP Manipulation (more than 20 lawsuits and $3 billion recovered) to Medicaid rebate fraud ($183 million jury verdict as just one recent example) to overbilling the VA for generic drugs ($32.3 million settlement), whistleblowers have repeatedly shined light on the myriad ways that drug prices are vulnerable to manipulation and lead to increased government spending. And the government has recovered billions from pharmaceutical companies as a direct result. While it remains to be seen what will happen with Part D’s price negotiations, it is clear the government will need whistleblowers to protect this new program like the others that have come before it.

Kate Scanlan is a Founding Attorney at Keller Grover, LLP