Protect Declined Qui Tams; Protect Taxpayers

In our September 2 post on the troubling decline in False Claims Act –recoveries in recent years, we highlighted the growing importance of declined False Claims Act cases in recovering government money lost to fraud. “Declined cases” are FCA cases brought by whistleblowers under the qui tam provision where the United States Government has “declined” or decided not to take over or “intervene” in the case, and the whistleblower proceeds to litigate the case without the government as a party (although the government is still the “real party in interest”) as specifically contemplated by the False Claims Act.

In a declined case, whistleblowers are often going up against huge companies with well-funded litigation counsel. The pre-trial motions and discovery phases of declined cases can take years and require thousands of hours of attorney time and millions of dollars in costs for everything from depositions to experts.

In court filings DOJ has made clear that when they decline a case, it does not mean the whistleblower is wrong. Indeed, one reason the government may decline to intervene in a case is because DOJ trusts the whistleblower and their lawyer to prosecute the non-intervened case. This is why whistleblowers receive a larger share or bounty when they win a declined case under the FCA.

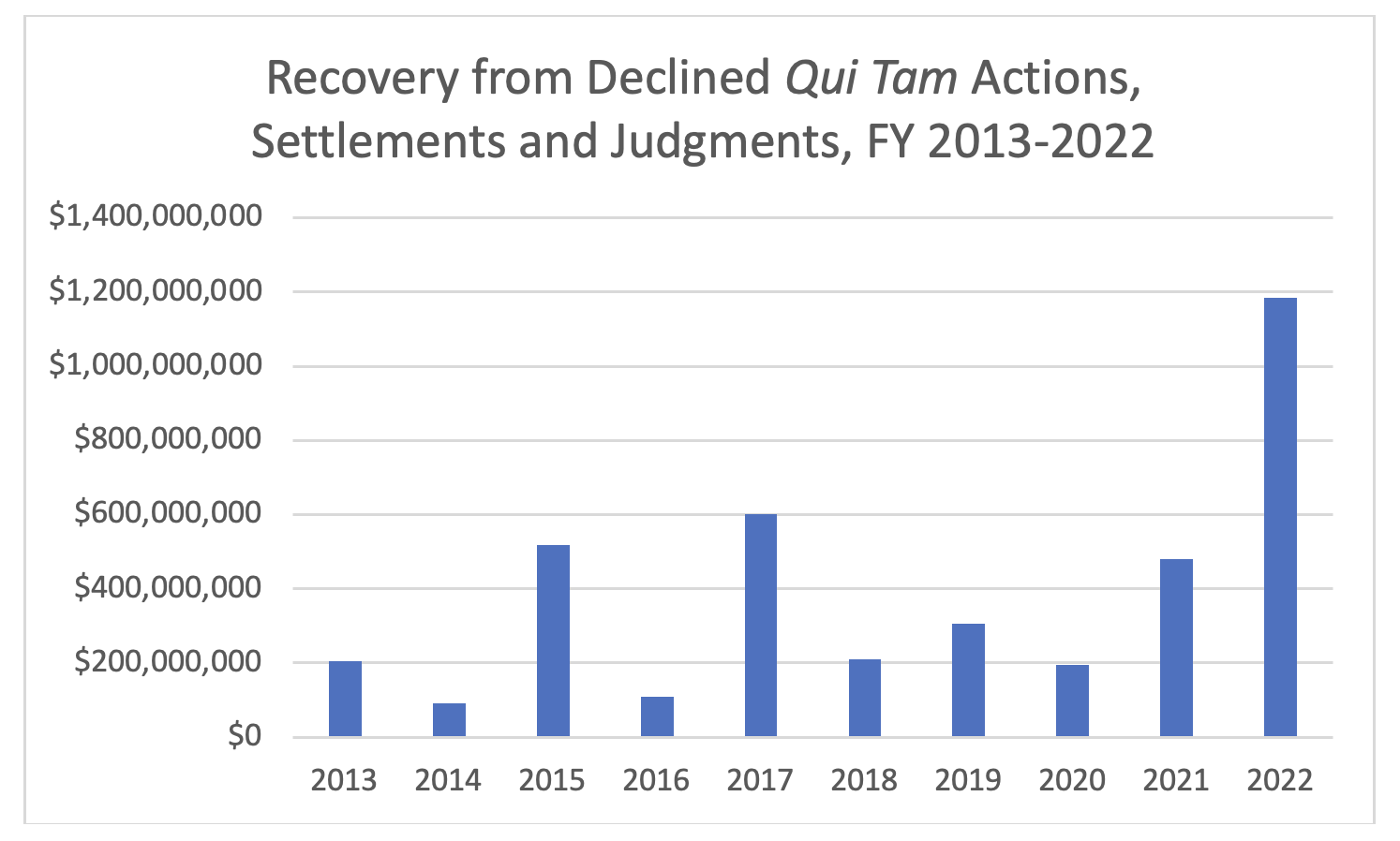

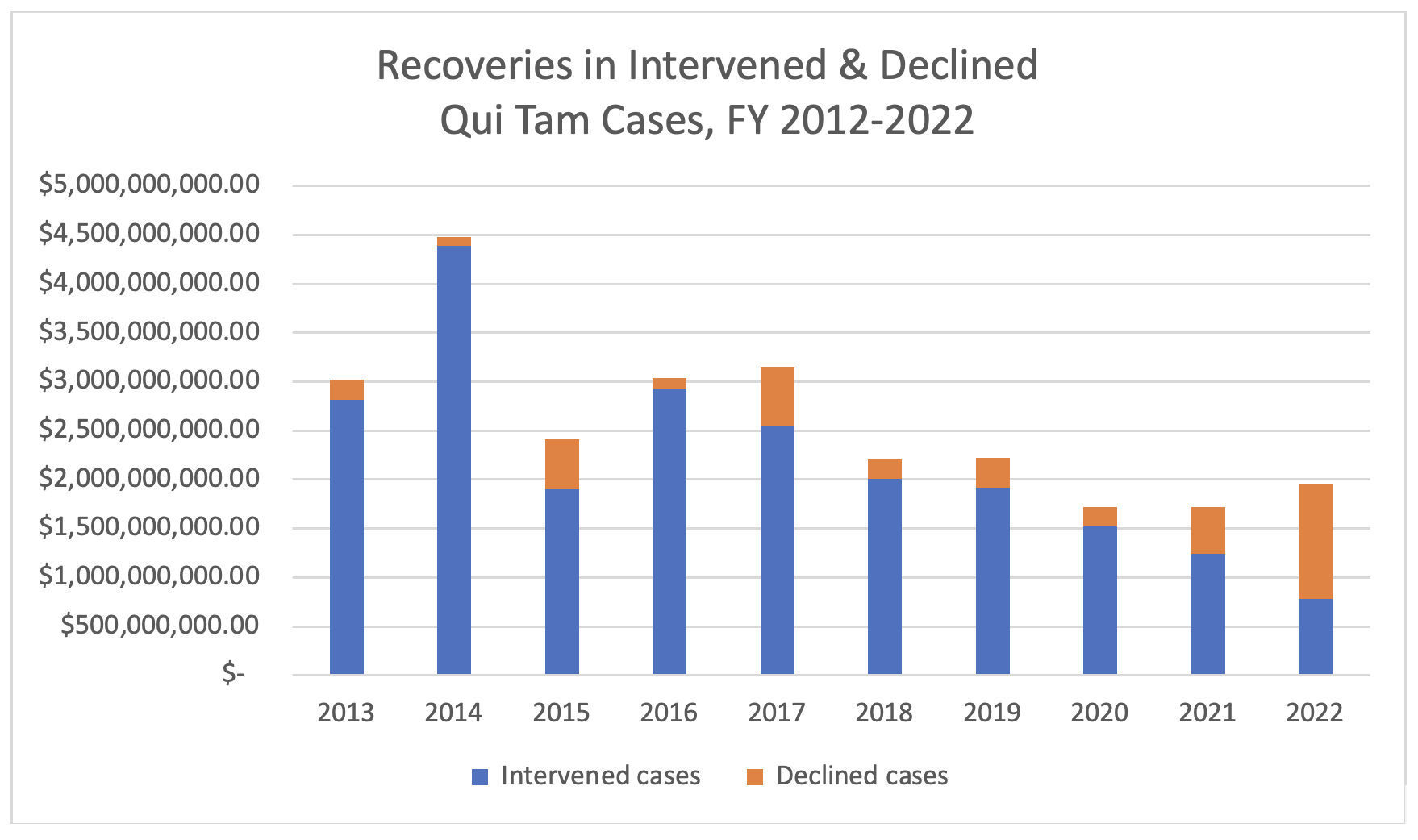

Despite their challenges, declined cases recover hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars each year, and their value to the public fisc is growing even as the government’s resources are stretched thin.

In fact, in 2022 declined cases were so successful that they recovered more money—about $1.184 billion—than False Claims Act cases intervened in and settled or prosecuted by the government in that year (about $1.02 billion).

The massive 2022 recovery from declined cases was largely due to a single declined case alleging kickbacks to physicians by pharmaceutical company Biogen that was resolved by settlement on the eve of trial for $900 million after seven years of litigation. This settlement alone was about 40.9% of the total amount recovered by the government in 2022 from FCA cases (about $2.2 billion). It was also about 51.1% of the total amount recovered by the government in healthcare fraud cases (about $1.761 billion).

Notably, however, declined cases were also an unusually large share of Department of Defense-related recoveries in 2022, with $28.7 million recovered in declined defense spending cases out of a total of $103.7 million recovered by the government. That means about 27% of defense money recovered from fraudsters in 2022 was through declined qui tam actions.

In all, 2022 was an extraordinarily successful year for declined cases, amidst lackluster overall numbers for False Claims Act cases. Perhaps that explains the motivation for False Claims Act defendants to opportunistically renew a challenge to the constitutionality of the False Claims Act’s qui tam provision—an issue put to rest more than 30 years when the Act was amended.[1] The FCA was designed to empower whistleblowers to pursue fraud when the government lacks the resources to do so, which is exactly what happened last year.

Nicolas Mendoza is an Associate at Murphy Anderson PLLC

[1] A recent dissent by Justice Clarence Thomas in a declined False Claims Act case before the Supreme Court suggested—with little support—that declined cases might be unconstitutional because they are not under the direct control of the government. No other justice joined Justice Thomas in his musings. As a result, FCA defendants have started raising constitutional challenges to the statute in district courts around the country.