Open Enrollment for Medicare Advantage Plans is Not Open Season for Fraud

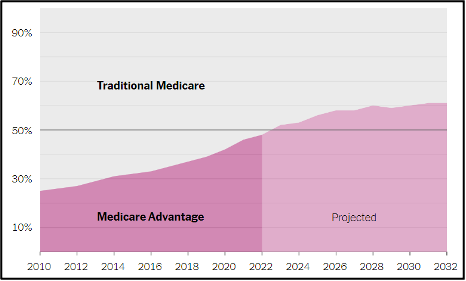

Medicare and Medicaid, the nation’s largest taxpayer-funded health insurance programs will be mostly in the hands of private insurers by 2023.[1] This privately-run system goes by different names: Medicare Part C, Medicare Advantage, or managed care. The government spends nearly as much on managed care as it spends on funding the U.S. Army and Navy combined.[2] Household names such as UnitedHealth Group, CVS Health, Kaiser Permanente, and Cigna act as passthroughs or intermediaries of health care funds, collecting administrative or management fees. While Medicare and Medicaid patients still have the option to stick with their traditional plans, the private insurers have recruited patients in record numbers, thanks to their aggressive marketing.

But buyers should beware. The financial incentives have proven to be an enticement for some greedy players in the managed care industry. Relators (whistleblowers) have brought False Claims Act qui tam cases to shed light on abuses. Pursuing these cases, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has focused initially on the private insurers who allegedly inflated capitated payments from the managed care programs by falsifying patients’ diagnoses (making patients appear sicker than they are).

DOJ and relators have pursued False Claims Act cases against at least 5 of the top 10 Medicare Part C providers; and the watchdog of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, its Office of Inspector General (OIG), has issued audits, finding at least 8 of those top organizations have overbilled Medicare.[3] This trend will continue, the Department of Justice has already defeated an insurer’s motion to dismiss in 2023, with a whistleblower-initiated case against Independent Health proceeding in the Western District of New York.[4]

While the private insurers and their extensive networks of health care providers and subcontractors are facing increasing FCA liability in the managed care context, they simultaneously remain liable for traditional FCA fraud schemes such as excessive billing, upcoding, medically unnecessary services, and violations of Anti-Kickback Statute (AKS). Managed care claims are properly recoverable under all traditional FCA theories holding them liable for schemes that lead to the submission of false claims paid by the government.

Indeed, defendants in managed care cases have settled not only new schemes that arise in the context of managed care (such as capitated payments and falsified diagnoses), but these old schemes as well. And DOJ has shown that it will continue to enforce the False Claims Act for new schemes arising under managed care as well as for the old schemes, a recognition that FCA liability for excessive or tainted claims includes any claims for payment submitted by the provider, whether those claims are for patients insured through traditional Medicare and Medicaid, or managed care.[5]

One recurring defense theory that has been refuted is that there can be no falsity because there is no “claim” under the managed care program.[6] “[T]he FCA does not limit ‘claims’ only to payment requests submitted directly to the Government, see 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b)(2)(A)(i); instead, ‘claims’— as defined in 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b)(2)(A)(ii) — also can include requests submitted to entities like Part C plans that receive funding from the Government to operate federal programs like Medicare.”[7] A “claim” thus includes both “direct requests to the Government for payment as well as reimbursement requests made to the recipients of federal funds under federal benefits programs.”[8] Managed care still requires health care providers to submit claims on behalf of their patients, and if those claims are false, the False Claims Act applies.

The seismic shift of Medicare and Medicaid patients to private insurers does not absolve the insurers or health care providers from FCA liability for committing the same old fraud schemes just because they have also found new ways to defraud these taxpayer-funded programs; they will continue to be accountable to the American taxpayer.

Eva Gunasekera is a Partner and Jaclyn Tayabji is a Public Interest Fellow at Tycko & Zavareei LLP

[1] Reed Abelson & Margot Sanger-Katz, ‘The Cash Monster Was Insatiable’: How Insurers Exploited Medicare for Billions, N.Y. Times (Oct. 8, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/08/upshot/medicare-advantage-fraud-allegations.html.

[2] Reed Abelson & Margot Sanger-Katz, ‘The Cash Monster Was Insatiable’: How Insurers Exploited Medicare for Billions, N.Y. Times (Oct. 8, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/08/upshot/medicare-advantage-fraud-allegations.html.

[3] Reed Abelson & Margot Sanger-Katz, ‘The Cash Monster Was Insatiable’: How Insurers Exploited Medicare for Billions, N.Y. Times (Oct. 8, 2022), https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/08/upshot/medicare-advantage-fraud-allegations.html.

[4] United States ex rel. Ross v. Independent Health Corporation, 2023 WL 24055 (W.D.N.Y. Jan. 3, 2023) (No. 12-cv-299s)

[5] See, e.g., Press Release, Private Equity Firm and Former Mental Health Center Executives Pay $25 Million Over Alleged False Claims Submitted for Unlicensed and Unsupervised Patient Care, Mass. Office of Atty. Gen. (Oct. 14, 2021), https://www.mass.gov/news/private-equity-firm-and-former-mental-health-center-executives-pay-25-million-over-alleged-false-claims-submitted-for-unlicensed-and-unsupervised-patient-care. See also Complaint in Intervention of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, U.S. ex rel. Martino-Fleming v. South Bay Mental Health Ctr., Inc. et al., No. 15-CV-13065 (Jan. 5, 2018).

[6] See, e.g., Statement of Interest of the United States of America, U.S. ex rel. SW Challenger LLC et al. v. EviCore Healthcare MSI, LLC, 2021 WL 3620427 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 13, 2021) (No. 19-2501).

[7] Statement of Interest of the United States of America at 5-6, U.S. ex rel. SW Challenger LLC et al. v. EviCore Healthcare MSI, LLC, 2021 WL 3620427 (S.D.N.Y. Aug. 13, 2021) (No. 19-2501). See also Complaint in Intervention of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts at ¶¶ 75-76, U.S. ex rel. Martino-Fleming v. South Bay Mental Health Ctr., Inc. et al., No. 15-CV-13065 (Jan. 5, 2018) (“Massachusetts regulations do not distinguish among MassHealth beneficiaries who receive MassHealth benefits via FFS [fee for service], MassHealth beneficiaries who receive MassHealth benefits via MBHP [Massachusetts Behavioral Health Partnership], and MassHealth beneficiaries who receive benefits via MCOs [Managed Care Organizations]. . . . Consequently, payment for these services, whether the claims are submitted to MassHealth directly or through MBHP or one of the MCOs, comes from the Massachusetts Medicaid program.”).

[8] Universal Health Servs. v. U.S. ex rel. Escobar, 579 U.S. 176, 182 (2016) (citing 31 U.S.C. § 3729(b)(2)(A)).